|

|

||||||||

| Veterans, Our Unassuming Heroes | |||

|

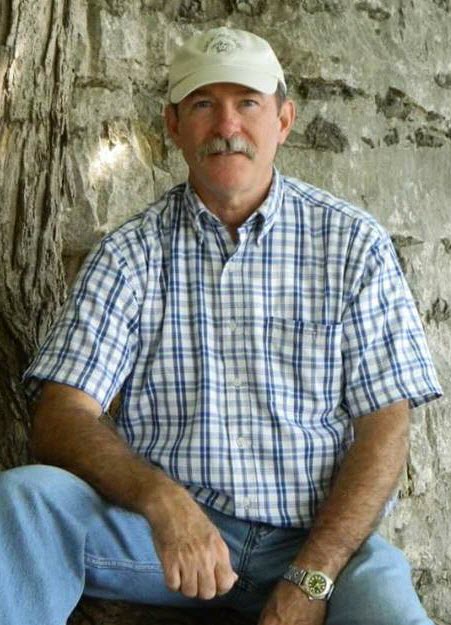

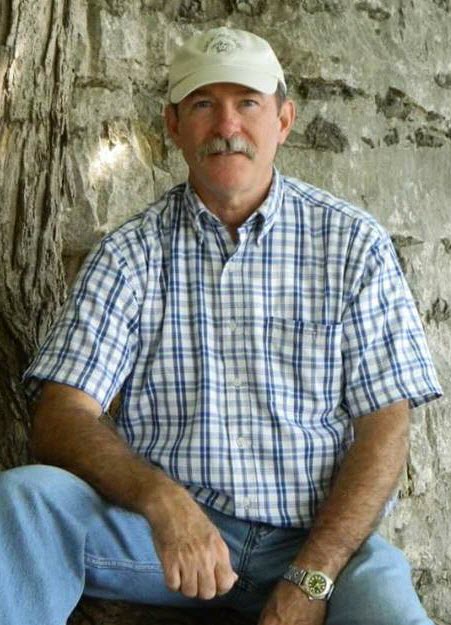

If ever asked who I considered my hero, I would have to say it was my father, Harold Algood. He was a quiet, unassuming man

who spoke little, but when he did, he spoke words worth heeding.

He was in the midst of a fall harvest on the family farm west of Louisville, Mississippi when he received notice his country

needed his service in the war against Hitler. He requested only enough time to finish the harvest before reporting to boot camp.

His widowed mother was left behind to operate the farm in his absence. Daily, he wrote letters to her telling about his new

life in the military and giving instruction on what needed to be done day-by-day to keep the farm going. I still have most of

those letters, and it has been interesting reading them because they tell what he was thinking and experiencing between 1943

and 1945.

There were hidden clues in those letters that let my grandmother know his whereabouts throughout the war. Some tell of the

weather conditions, which let her know approximately what country he was going through. Others indicated if he was sleeping

on “hay” or in a tent. Those letters told her whether or not he was able to take shelter in a barn, or building, or if he was

on the move and out in the open.

Not once did he mention the actual war. That was probably forbidden. He would mention if he was eating rations or if he had

eaten a good meal. That, too, was an indication of being in combat or if there was a lull in the war where they had time to

set up the mess tents. In some letters, he mentioned that he had received boxes of food or clothing from home. And in other

letters he let her know he was sending packages home so she could watch for them.

The first postmark I found was from Junction City, Kansas, dated February 11, 1944. The next letter indicated he was at Fort

Riley, Kansas.

In May of 1944, the postmarks were from Camp Gordon in Augusta, Georgia. Then in June of ‘44 he was sending letters from New

York, an indication he was being shipped over seas. He was in England briefly before landing in France.

He was in Patton’s Third Army and was a lookout gunner on a Sherman tank. On July 6 his outfit landed on Normandy Beach. They

attacked the German left flank at Normandy and in August of `44 they were moving 40-50 miles a day across France. They went

through Metz and hit La Range.

He was there during the worst winter in thirty eight years, and the Third Army was moving so fast they out-ran their supply

line. On December 16, 1944 they were attacked by the Germans. It was there both of his ear drums burst from shells exploding

around his tank. They were at the Battle of the Bulge, the Ardennes Mountains and in Belgium.

The day after Christmas he was in the Battle of Bastogne. They crossed the Rhine River and moved to Aire, then on to Burgermister

to liberate a concentration camp.

Germany surrendered on May 7, 1945. After the war, he returned home with a dog he named, Yank, that he had befriended and carried

with him throughout the war to resume farming in Calvary Community, west of Louisville.

On December 4, 1945 he married my mother, Rochelle Foster, in a double wedding ceremony with his cousin, Otera Bennett and her

fiancé, Nowell Haggard, at First Methodist Church’s parsonage in Louisville. His brother, Reuben, was the only witness for both

couples.

Like a lot of veterans from that war, my father seldom spoke about his service. I am certain those men saw things they never wanted

to think about again. Though he did tell my brothers and me stories about a few lighthearted moments, he never spoke about the

dirty business of war. I learned a few of those stories long after he had passed away. My uncle, Reuben Algood, shared them with

me.

Shortly after returning home my uncle, who served in the Pacific Theatre, and my father who served in the European Theatre, sat

up late one night sharing their personal accounts of what happened on both war fronts. My father told him he would talk about it

that night, but after that he did not want to think about it ever again. I have to testify he was true to his word.

The stores I learned of his service were learned from my uncle, digging through his war records, and reading a lot of history

books about the movements of the Third Army.

One day my father’s tank was sent beyond the front lines to scout for the enemies. They had traveled several miles and came upon

a hedge row. Beyond the hedge row the Germans were on the move. They were upon them before they realized it. Immediately, they

turned the tank around to retreat back to their outfit, and when they did, the track came off one side of the tank.

That was nearly a fatal mistake. They radioed back to get help putting the track on, but were told it was too late in the day and

they would have to hunker down for the night and make it the best they could. Darkness fell and they drew straws for guard duty. My

father drew first and last watch.

After his first watch, he got back in the tank and settled in for the night until his next watch. He said when he woke up sunlight

was coming through a seam in the tank and striking him in the eyes. He knew he had overslept and wondered what had happened to his

buddy that was on guard. Somehow, he was able to peer outside and saw five Germans approaching the tank with their guns drawn and

pointed at them.

He did the only thing he knew to do. He yelled out “Halt! Throw down your weapons!”

Surprisingly, they obeyed.

When he yelled out it woke his buddy who was on the opposite side of the tank. He stood up and came around the tank to see five

Germans with their hands in the air.

He held his gun on them until my father and the other soldiers climbed out of the tank and got their weapons.

The Germans were made to help put the track back on. After the track was on, they tied them around the outside of the tank, and

drove back to rejoin their outfit.

When they rejoined their unit they were nearly court-martialed for bringing prisoners back with them. Their company was on the

move and had no time for prisoners.

Another time my father’s tank became separated from its outfit during battle and they were trying to catch up with them. According

to the information they had received, their outfit was on the other side of a large hill. They decided to take a short cut over

the hill to catch up with them. They made it up the hill and were going down the other side when the tank began to slide sideways

and tumble over. Somehow they were able to get control of it and caught up with their unit.

When they got back into formation the commanding officer asked them how they managed to catch up so quickly. They told him they

took a short cut over the hill behind them. He informed them they could not have done that and demanded to know how they got there.

Again, they told him they had come over the hill and caught up with the outfit. It was then the commander looked down and began to

shake his head. He told them they had to be the luckiest “S.O.B.s” on earth. The hill had just been planted with mines so the

Germans could not cross it and attack them from behind.

Once they came to a town and took over a big house. There was a large footed bathtub in an upstairs room. However, there was no

running water in the town.

They brought the tub downstairs and cut a hole in the floor where the drain was. Then they hauled water inside and heated it up for

a bath. When they had finished bathing they pulled the plug and the water drained out into the basement.

There was a beautiful dining room in the house and they set it with fine linen, china and sterling silverware. They ate a huge meal

and then the commander said it was time to do the dishes. The men all stood up and grabbed the table cloth in front of them. They

marched it over to a large window and tossed the table cloth, dishes and all out the window.

He told my uncle it was the quickest he had ever done dishes.

Once he said they came into a German town on a cold night. They had been fighting for days and had driven the German Army out of

the area. They walked up to a house and ordered everyone to leave immediately. The occupants all grabbed their clothes and some

belongings and fled the house.

My father said he found a bed and climbed in. The occupants had left so quickly the sheets were still warm!

His unit liberated a slave labor factory one day. When they opened the doors the building was filled with children the Germans had

conscripted into service. He said most of the children were about 12 years old. They were beyond happy to be set free.

People were carving up horses in the streets for food. It was bad. I am told he liberated a concentration camp. But, he never

discussed it as far as I know. I have come across photos of mass graves with bodies piled inside. I don’t know if he took the

photos or if he found them. There was a Rabbi at one end of the gravesite holding a service for those that filled the long trench.

Had my father had lived longer, he might have shared more stories about the war and some of his experiences. But I am afraid there

are many historical events he saw and experienced that we will never know about.

As I mentioned before his eardrums burst during combat. For years he had difficulty hearing. In the mid 1960s a hearing-aid was

developed that helped him. He went to the VA in New Orleans and was fitted with two hearing-aids.

One night soon after he received them we were sitting on the front porch and I noticed Daddy playing with them and trying to adjust

the volume. Then he just sat there in a daze. He asked us, “Do you hear that?”

We had not noticed anything out of the ordinary and answered, “No.” We had not heard anything.

Then we noticed he was almost in tears. He said, “Whip-O-Wills! I can hear Whip-O-Wills! I have not heard those since before

the war.”

We had taken the sounds around us for granted. There were things he was able to hear after that, that he had forgotten about in all

those years after the war.

After he passed away I found the following information among his papers. Army serial #. He was a Tec 5 and entered service October

28, 1943. He separated service October 21, 1945 at Fort Bragg. He was a private basic 521, private first class rifleman 745, Tec 5

Cannoneer 1736 and Tec 5 Assault Gunner 1736.

He was an assault gunner with the 3rd Calvary Reconnaissance Squadron (Mechanized). Fired a 75 MM Howitzer mounted on an M8 motor

carriage, employing both direct and indirect fire support of armored car and light tank reconnaissance groups. He also fired in support of infantry… particularly during the crossing of the Mosselle River in France. My father was in combat during four major campaigns and had 269 days of continuous combat. He fought in the European Theater of Operations, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes and in central Europe. He received the following decorations: Eamet Campaign medal with four Bronze service stars, Good conduct medal GoII HQ 3 Cav RCN SQ 24 DEC 44.

While researching my first book, I learned my father’s fellow crew members in the Sherman Tank were Wayne E. Smith of Halstead,

Kansas, Stan Johnson of Reading, Massachusetts, and James Jennings of Helena, Montana. Sadly, after they departed service at Fort

Bragg they were never able to reunite.

The older I get the more I realize I owe so much of the things I have taken for granted to men like my father who fought and died

for this country. It’s like I’ve heard before somewhere, Freedom isn’t Free.

We owe all the veterans so much. They are all heroes of in their own right. But as for me, I lived with one for two decades and

never realized it at the time. I am remorseful for that.

Daddy, you will always be my hero, and I will never fail to tell the next generations in your lineage about what you did for

all of us.

Thank you.

_______________

|

|||